Barbara Higham on why she believes we are in the grip of a tongue-tie epidemic and how this disempowers mothers and damages their babies.

This article is written in the role of investigative reporter and from my perspective as a mother and breastfeeding advocate. I hope you find what I say is thought provoking.

What follows incorporates most of what I said in my presentation, with some additions, particularly to the list of references, last updated May 2021.

I have no conflicts of interest and my work on this topic is done on a completely voluntary basis.

My message is that babies are vulnerable—they can’t make decisions for themselves—and it’s our duty to keep them safe from harm and not subject them to surgery where there is no good reason to put them through it.

I’m going to examine:

- Tongue-tie as a modern epidemic.

- The politics and ethics of the situation.

- What tongue-tie is, how it’s assessed, and diagnosed.

- The research: what’s reliable and what’s conjecture.

- How ties disempower mothers and damage babies.

If you work with mothers and babies or advocate for them in connection with birth or breastfeeding, you’ll have heard tongue-tie discussed and with increasing frequency over the last few years. The condition has sparked considerable controversy that’s far reaching and raises a lot of questions. I want to draw attention to those questions.

A modern epidemic

Are we in the grip of a tongue-tie epidemic?

What is the prevalence of tongue-tie (that’s the proportion of total cases in a population)? And is the incidence (that’s the occurrence of new cases) increasing or is it simply being identified more often? Last September, the journal Clinical Lactation asked tongue-tie experts these questions.

Alison Hazelbaker who specializes in the treatment of infant sucking problems, wrote one of the earliest books on tongue-tie, and created the Assessment Tool for Lingual Frenulum Function says, ‘According to the current body of evidence, prevalence rates range from 0.1% to 10%, clustering around 3.5%–5%.’

When asked the same question, Martin Kaplan, a paediatric dentist in Massachusetts, who was an early adopter of laser dentistry, said the percentage was ‘as high as 25% in infants with breastfeeding problems.’ When asked if the incidence of tongue-tie was increasing, he said, ‘I now see hundreds of babies for necessary treatment. So, the incidence to me suddenly went from zero to hundreds a year. Based on the number of referrals to my practice, over 90% have a tongue-tie.’ He went on, ‘The current IBCLC and social-media infant referrals are coming to me because they have exhausted the simple fixes that help with breastfeeding’. It’s not clear how he defines ‘exhausted’ nor why he’d assume fixes are necessarily ‘simple’.

Christina Smillie, respected paediatrician and speaker on the clinical management of a wide variety of breastfeeding issues, said, ‘The recent increased diagnosis of posterior tongue-tie may reflect an increased enthusiasm for the diagnosis more than an increased incidence of actual restricted function’.

James Murphy, who used to be a physician in the U.S. navy and is on all sorts of prestigious boards, boasts that in his practice, Breastfeeding Fixers, in California, he has performed more than 4,000 of these procedures and more than 600 upper-lip frenotomies. He estimates the ‘true incidence’ to be roughly 20%–25%.

Pamela Douglas, associate professor and senior lecturer at the University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia, says that attempts to quantify incidence have remained of very poor quality, but estimates between 4 and 10%. She says, ‘Classic tongue-ties are now much less likely to be overlooked but all research into tongue-tie since 2005 is compromised due to a lack of definitional clarity concerning the diagnosis. Anterior tongue-tie is conflated with “posterior” tongue-tie, because providers claim that behind every anterior tie there lies a posterior one.’

Is the incidence of tongue-tie increasing? Why are health professionals identifying ties more often?

The figures suggest either a big increase in the number of faulty babies or that there’s currently an epidemic of over diagnosis and over treatment.

- Canada has seen an 89% increase from 2004 to 2013 (Joseph, Kinniburgh, Metcalfe, Razaz, Sabr, & Lisonkova, 2016).

- In Australia, between 2006 and 2016, there was a 420% increase in the rate of frenotomies per 1,000 children aged 0 to 4 years (Kapoor, Douglas, Hill, Walsh, & Tennant, 2018).

- Similarly, in the U.S.A. there has been an 834% increase between 1997 and 2012 (Walsh, Links, Boss, & Tunkel, 2017).

- In the U.K., it is hard to put a percentage on the provision of frenotomy. NHS availability to tongue-tie practitioners varies widely and the provision by independent practitioners is unrecorded in any official statistics, as well as being an unregulated service. Frenotomy is certainly happening very frequently here.

This skyrocketing of the number of diagnoses is peculiar to high-income countries, where over treatment has been recognised as a serious problem in the provision of health care. What Hoffmann & Del Mar, 2017 (researchers in evidence-based practice) call ‘an unjustified enthusiasm’. You don’t need to be an epidemiologist to conclude that these patterns are typical of over treatment. It makes no sense that so many babies have abnormal frena.

Editor’s note (May 2021). Between 2009 and 2018, the number of tweets about ankyloglossia and frenotomy increased by 2395%! (Grond, Kallies, & McCormick, 2021). This study’s findings demonstrate the spectrum of opinions that exists among both parents and health providers about tongue-tie. The authors found that a large amount of non-scientific information and opinion is disseminated via twitter that may be shaping decisions on tie surgery. It would be interesting to conduct such a study on Facebook data.

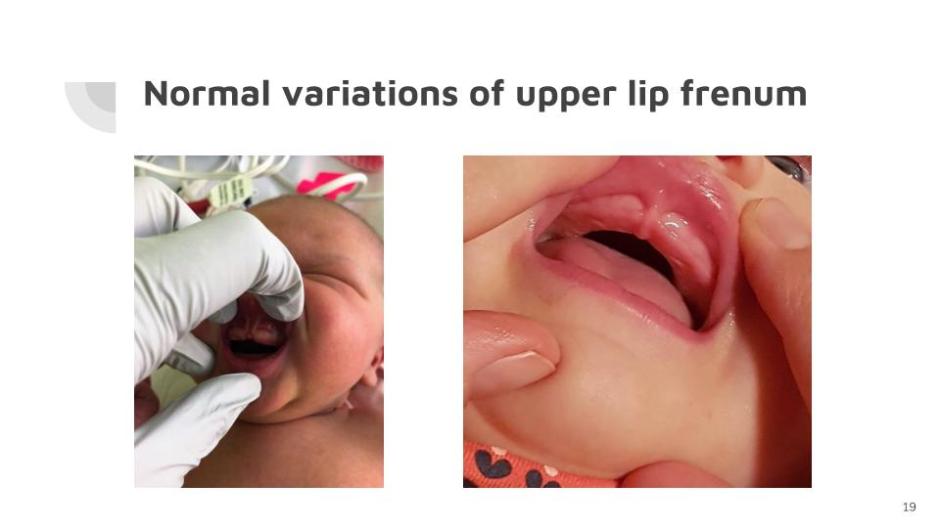

Tongue-tie proponents claim that the condition had been largely overlooked in the past, ignoring that for more than 99% of our existence as a species, all human infants have obtained their main nutrition through breastfeeding and as mammals we have an evolutionary history of lactation that is even more ancient. In the past, breastfeeding was a universal natural imperative. This evolutionary history as a species shows that tongue-ties make no real difference to whether babies breastfeed or not. If they did, where is the evidence of the high number of babies who would have died in the past from starvation as a result of tongue restriction? What we actually have is a gloriously wide range of normal variations of the frenum.

The frenum is what ties the tongue. This tissue is what restricts the motion of the tongue. It secures the motion of the tongue too and functions as a protective connective anchor. These tissues (or frena) connect the tongue to the floor of the mouth and the lips to the gum, and the cheeks to the gum.

Tongue-tie is usually described as a ‘congenital abnormality’, so that’s something you’re born with and which may or may not be inherited, and this ‘tie’ label is used when the frenum appears to limit the range of movement of the tongue, when this restriction is judged to be interfering with feeding (or speech).

While it’s commonly agreed that these tethers may cause feeding issues, they are not the cause of the majority of breastfeeding challenges. And in most cases there are breastfeeding solutions to breastfeeding problems. Babies with ties can breastfeed successfully. One study (Power & Murphy, 2014) says 50% have no trouble breastfeeding and I’d put it considerably higher than that, at least where the idea of ties hasn’t already been planted in a mother’s head.

It should go without saying that if a mother-baby pair is able to breastfeed comfortably when the baby has a prominent frenum (and many do) then this is not actually a ‘tie’ and requires no intervention.

I have permission to share this mother’s story and photo of her five-year-old with you.

He breastfed well from birth. Found his own way to the breast in about 40 minutes. No nipple pain for me. I didn’t notice his tie until he was a few months old. He’ll be 6 soon and he’s still breastfeeding. I never had a single issue. No pain, no blocked ducts, great supply. No history of tooth decay, teeth all good apart from the top baby tooth that he knocked out in a fall. No speech or airway issues.

I’ve heard similar stories from other mothers, some of them did struggle to initiate breastfeeding (as so many mothers do) but they got there in the end.

Award winning lactation expert Pamela Morrison IBCLC said:

I worked in a country where 93% of babies were still breastfed at a year, and moderate tongue-tie did not interfere with that, or even feature at all. I did not see a tongue-tie severe or tight enough to preclude breastfeeding, ever. So increasing breastfeeding rates around the world cannot be the reason for more diagnoses.

The politics and ethics

Tongue-tie really deserves a new chapter of its own in the politics of breastfeeding. If you’ve not read Gabrielle Palmer’s books, The Politics of Breastfeeding and Why the Politics of Breastfeeding Matter, I recommend them. Palmer describes how a thirst for profit systematically undermines a mother’s confidence in her ability to breastfeed and challenges our complacency.

There are some striking parallels between the promotion of artificial baby milk and of tongue-tie surgery. These few sprung to mind when I read those books.

- How in the last century, it’s a sad fact that the more contact mothers have had with health workers the less they have breastfed. (Please don’t stop trying!) But where are the data? We’re not seeing improved rates of breastfeeding in line with these higher rates of tongue-tie surgeries. A causal link between the two has not been established, which I shall come on to later.

- How it is often easier, and more lucrative, to work out a stopgap way of alleviating a problem than it is to discover why it occurred in the first place. Mothers are desperate for action, they want a quick fix for their sore nipples or their baby’s colicky symptoms, and (as one expert said) in the current environment, where everyone is worrying about ties, health professionals feel the need to respond pragmatically. In other words, they feel compelled to act! A scissors frenotomy is apparently a low risk procedure with limited short term implications; no-one really knows if it will help—why not cut it and see?

- Our reliance these days on technological solutions and how women in industrialised countries crave instructions as a direct measure of their lack of confidence. We Google everything, don’t we, for ‘how to do this or that’, ‘10 tips to become a brain surgeon’. Back in the 1950s, doctors persuaded mothers that artificial feeding with formula milk was ‘scientific’. The gobbledygook they talked it up with was impressive. I’m thinking ‘tie savvy’ lingo with every second word straight from the medical dictionary. Obfuscatory language is typical of pseudoscience. ‘Advertising makes us feel we need something that previously we didn’t need.’ ‘Effective distribution of promotion by a universal means of communication creates a market’ (Palmer).

- How very often mistakes become sanctified because they are in print. As an editor, I’m aware of how things get picked up and repeated as truth. Google ‘tongue-tie’ and articles often start with the assertion that it is a congenital abnormality, when this has by no means been established. Along with the drive to market formula, breastfeeding failure became accepted as a common flaw in women’s bodies, and now tongue-tie is becoming accepted as a common problem in infants’ mouths. Where are mothers able to find consistent and impartial information? Informed choice is the mantra of western society and is seen as a right, but are parents fully informed? I’ll come to what ‘information’ we have later on.

- How the medical profession strives to be neutral, yet manages to ignore the integration of commercial interests with medical issues. I am not saying that the majority are not acting in good faith nor that it is wrong to make a living from treating patients. Nevertheless, there are grey areas, like the fact that treating more patients can cover the costs of expensive new equipment. Some providers of tongue-tie surgeries now have flyers for handing out to pregnant women at mother and baby fairs. Here’s an interesting dilemma that recently (July 2018) came to my attention: In New Zealand, the largest private health care provider will refund a lactation consultant’s fee to its members when a frenotomy is performed, but not if the lactation consultant addresses a breastfeeding issue by offering guidance on how to improve positioning and attachment instead of recommending the surgical procedure—lactation advice is not recognised under the insurance policy terms. One can imagine, in some instances, that such a restriction could lead mothers to put pressure on the lactation consultant with regard to how to fix the problem, particularly when they are already being urged to go along the surgical route by the vast majority of social media tie support groups.

- The confusion between philanthropy and vested interest and how many are so caught up in the whirlwind of career progress and profit seeking that they seem unable to review the damage they do. And tongue-tie surgery can cause damage. I hope this is less of a concern in the UK, where we are still fortunate to have a national health service. In the health care arena, however, some are promoting tie surgery on social media, even using photos of cute babies in their arms together with assertions of how relaxed they are. This is exploitative and unconscionable.

In her book The Politics of Breastfeeding, Palmer notes that in spite of the lack of evidence that the ingredients in formula are essential or even safe, no company has ever put a label on the tin that reads,

This product is as yet unproven to be completely safe, thank you for letting us use your baby as a guinea pig.

She rightly judges experimentation on babies to be unethical.

We genuinely love to see mothers and babies master breastfeeding. One paediatric dentist commented, ‘It is not so much kickbacks but the club of “feel good” when they believe they are saving mothers and babies from a life of hell.’

And who is responsible for diagnosing ties? There has been a proliferation of opportunities for ‘education’ on ties: conferences, symposia, and ‘master’ classes, webinars at which advocates of these surgeries sell their promotion and encourage professionals to further their beliefs. To show how much they care for these vulnerable new mothers ‘generous’ donations are being publicly presented by providers of laser surgery, a percentage per procedure carried out, to perinatal mental health charities that support mothers with postnatal depression. The opportunities don’t stop there. For just $30 you can now join a Facebook program, a mothers’ circle, for support on your tie ‘journey’. At least they are aware of the misery they foster.

Homeopathic remedies now exist specifically to help with the emotional and physical trauma involved in tongue-tie surgery, some of them come with an endorsement from lactation consultants. In New Zealand, laser dentists have teamed up with an enthusiastic IBCLC referrer. One GP wryly suggested the idea of a new formula milk designed for babies with ties. And there is now a ‘magical Minbie teat’ being marketed at mothers with tongue-tied babies. Tell me again how there is no bandwagon.

A growing number of health professionals are admitting they daren’t rock the boat over these speculative surgeries.

If you are bold enough to question tie enthusiasts (practitioners or mothers) on social media, you invariably get shouted down. Health professionals are told they are ‘not keeping up’ and are subjected to ad hominem attack: that’s a common tactic used by those selling snake oil. I’ve been accused of a lack of compassion (I’m weeping with the babies and their mothers). I’ve been accused of not being ‘tie savvy’. I’ve been banned from posting in most of the tie Facebook groups and I received emails from lactation consultants advising me against speaking at the Midwives and Mothers Alliance conference: I am accused of ‘damaging reputations’ and putting livelihoods at risk.

Actually, Science doesn’t care whether you believe it or not. The truth will always be true and any theory needs to stand up to scrutiny.

Assessment and diagnosis

So what is tongue-tie? We have:

- No universally agreed definition of what constitutes a tie

- No standardisation of protocol for its assessment and

- No data to inform clinical decisions.

Parents are left to rely on widely differing clinical judgments. No clear distinctions exist between what’s pathological and what’s normal.

As we have already seen from the statistics, health professionals often diagnose frena as abnormal in infants with breastfeeding problems or unsettled behaviour, and refer them for frenotomy with scissors or laser. The widely accepted idea is that by cutting this tissue with scissors or eliminating it with a laser this will get rid of the restriction and in doing so make breastfeeding easier.

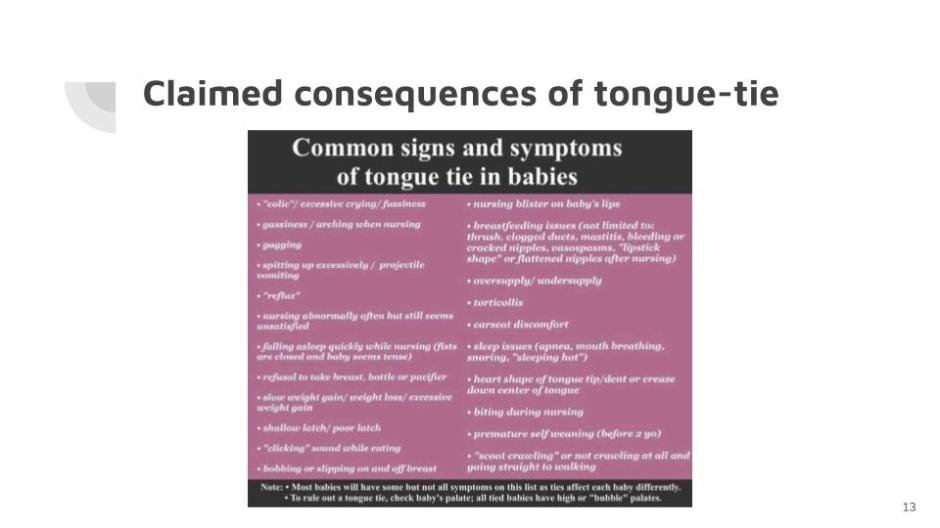

Signs and symptoms

If we take a look at a list of symptoms that some are attributing to the condition, we can see that many breastfeeding challenges are being associated with tongue-tie. This is just one example I pulled off Facebook. You can find other even longer lists.

It seems a bit of a leap to me to connect car-seat discomfort with tongue restriction.

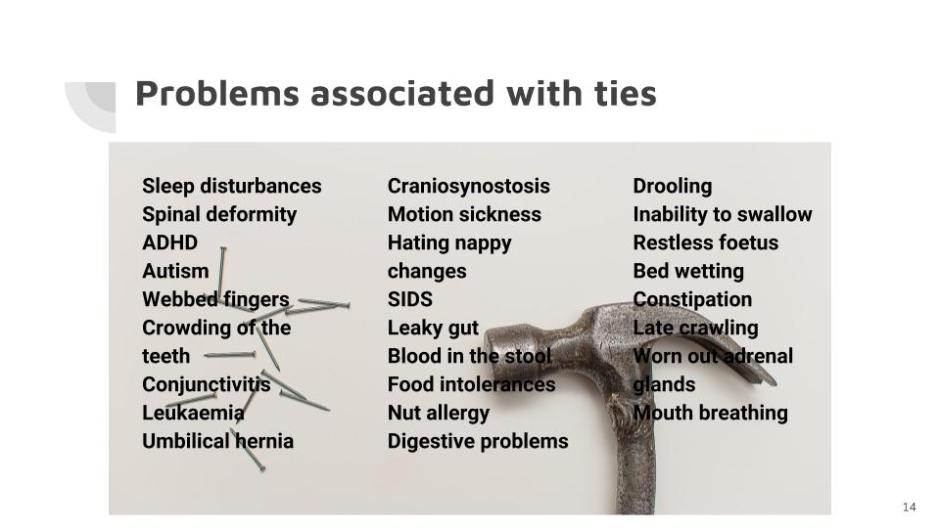

And I have seen a multitude of other ailments blamed on tied tongues: chest infections, rashes, asymmetrical muscular tightness, joint dysfunction, leaky gut, blood in the stool, food intolerances, nut allergy, difficulty eating, and digestive problems, drooling and inability to swallow normally, restless foetus, bed wetting, constipation, late crawling, worn out adrenal glands, mouth breathing and sleep disturbances, spinal deformity, defiant behaviour, meltdowns, ADHD and autism, webbed fingers syndrome, crossed toes, crowding of the teeth, conjunctivitis. One device on sale for training babies’ tongues lists a connection between tongue-tie and leukaemia in its marketing promotion. Umbilical hernia, craniosynostosis (that’s the premature fusing of bones in the skull), motion sickness and hating nappy changes, friction ‘blisters’, recessed chin, mental crease, overactive mentalis, perfectly normal milk-tongue, and even sudden infant death syndrome—all are, I’m told, associated with ties. [Have you noticed this list is growing?] Today (4th July 2019), I read one woman claim that her 89-year old mother’s dementia was caused by tongue-tie.

When all you have is a hammer everything looks like a nail.

Don’t ignore the possibility, too, that a baby may have a serious health issue that gets missed and wrongly labelled as a tie.

It appears that some people are jumping to conclusions and assuming

with tongue-tie.

Adults claim to benefit from having their own ties released to cure: headache and neck tension; improve balance, posture, and vision; correct erectile dysfunction, tight pelvic floor, and stress incontinence. Cutting the frenum can, some say, shorten the menstrual cycle and shrink nodules in the thyroid through some connection with pituitary function. Some believe it can even help with schizophrenia. One woman wrote that after the procedure, not only was her posture improved but her breasts were perkier too. There are some Before and After photos posted online which would be hilarious if they weren’t so sad.

Rather than associating all these things with tongue-tie, I prefer to apply Ockham’s razor, that’s the idea of the medieval philosopher, who supposedly said something along these lines,

When presented with competing hypothetical answers to a problem, select the one that makes the fewest assumptions.

In other words, the simple answer is more likely to be the right one. look for horses, not zebras.

look for horses, not zebras.

Anyone examining the mother-baby pair struggling to breastfeed needs to distinguish ties from other conditions that present with similar symptoms.

This requirement for differential diagnosis should use a standardised, valid, reliable, sensitive, screening tool/process.

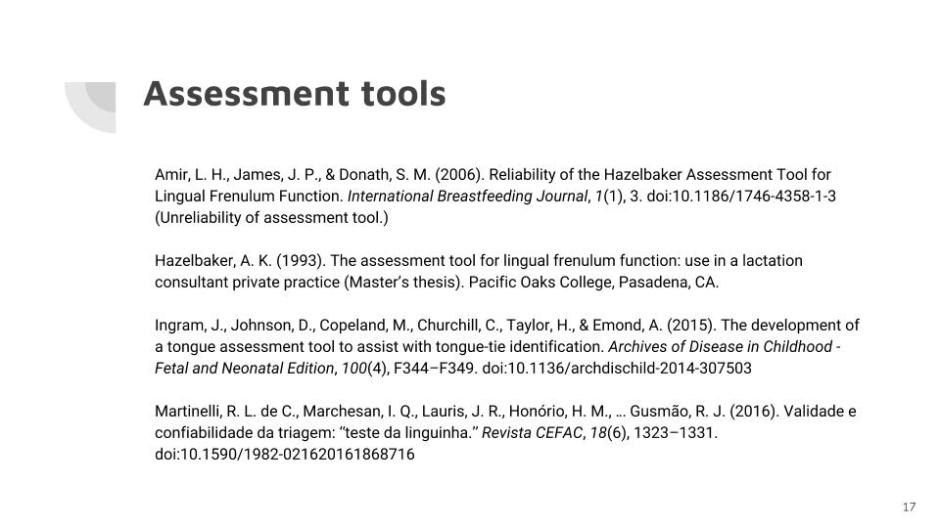

Assessment tools

There are a number of assessment tools, and a few of them are regarded by some experts as qualifying but are the subject of widespread disagreement. And a number of different classification systems that use a numerical description for where the ‘tie’ attaches to the tongue to describe if it’s anterior or posterior. Some health professionals who look in babies’ mouths say they find it virtually impossible to score the baby’s tongue using such a reductionist numerical approach, that this takes up a lot of time that could be better spent on clinical breastfeeding support. In practice, many of the item criteria of the tools are highly subjective and dependent on the baby’s level of cooperation during the assessment. Results can vary, I’m told, from one day to the next, even one hour to the next.

Lack of consensus

Health professionals do not agree on:

- how they assess for tongue-tie,

- how to proceed when it’s diagnosed,

- nor how to manage any subsequent wound treatment.

There’s no consensus amongst lactation consultants on what the role of the tongue is in effective breastfeeding and over explanations for how pain, injury, low milk supply, long and ineffectual feeds, and slow weight gain ‘fit with’ and explain breastfeeding problems with reference to ties.

The idea of posterior tongue-tie was only introduced in 2004 in a newsletter, not a research study at all (Coryllos, Watson Genna, Salloum, 2004). It was ‘rare’ for a few years and in 2010 in a retrospective case series, the authors state, ‘The diagnosis is difficult due to the subtle clinical findings’ (Hong, Lago, Seargeant, Pellman, Magit, & Pransky, 2010). But by 2011, paediatric dentist Lawrence Kotlow was describing using laser treatment to rectify it and introduced the idea that babies with tongue-tie swallow air, which has led to the idea that fussy babies may need tongue-tie surgery (Kotlow, 2011). That hypothesis ignores a considerable body of research on reflux. There is no evidence of babies swallowing air during ultrasound assessments. Refluxate is close to pH neutral for 2 hours after breastfeeds so doesn’t cause acidic discomfort (Douglas, 2013). Babies cry because of sensory need. Pick them up for goodness sake!

Labelling spitting up as a medical condition makes parents want medical intervention, even when they are told that treatment will not be effective. You might as well medicalise the fact that babies aren’t born walking.

There is a wide range of normal frena and what we can say with confidence is that the ones tethering the lip or the cheeks do not impact on function when breastfeeding. There is no reason to classify diverse variants as ‘upper lip ties’ or buccal ties. Systems for classification of the upper lip frena may be of anatomical interest, but lack any clinical relevance (Haham, Marom, Mangel, Botzer, & Dollberg, 2014; Santa Maria, Aby, Truong, Thakur, Rea, & Messner, 2017).

Despite claims, there is no evidence to suggest that frenotomy of upper lip and buccal frena helps with breastfeeding problems or protects against hygiene difficulties and tooth decay in later childhood.

The upper lip frenum has an extensive blood supply and many pain receptors. Cutting or lasering it inflicts pain. And doing so results frequently in trauma and oral aversion. Infants have been admitted to hospital with haemorrhaging or other serious complications as a consequence of the procedure. (Surgery on Babies: Does it Hurt?) See Why Upper Lip-tie Isn’t a Thing.

The research

Earlier, I said we have no data to inform clinical decisions. So what about the research?

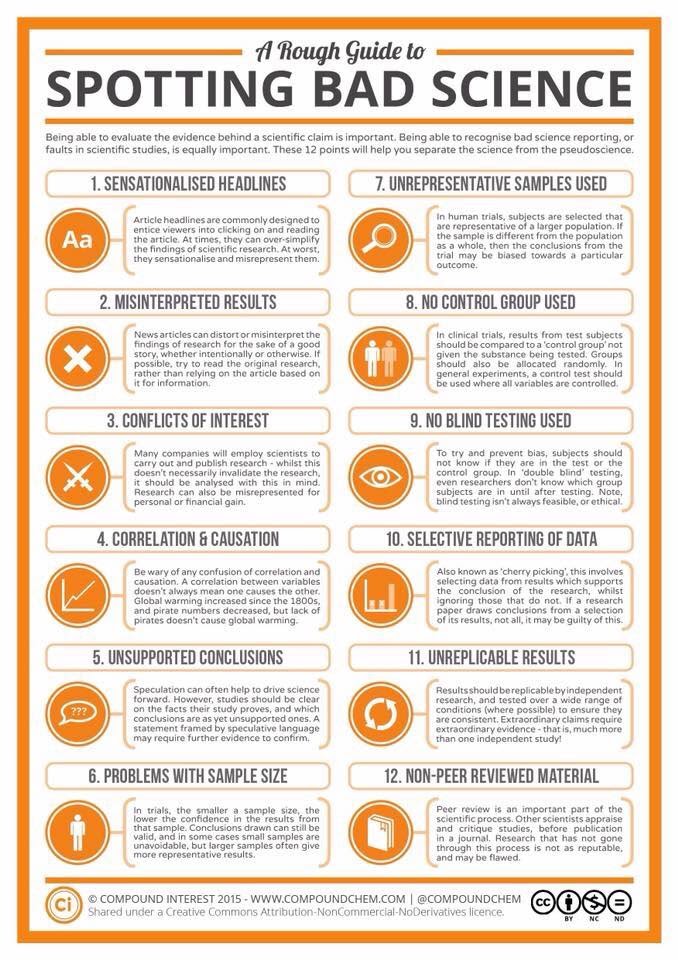

The International Affiliation of Tongue-Tie Professionals cites references for research studies as authoritative when other health bodies (including Cochrane and Australia’s National Health and Medical Research Council) cite the same references as very low quality based on no evidence.

The research that exists to support frenotomy confuses association with causation, failing to control for multiple potential confounders.

Interpretative bias may well have affected the reporting of data that fails to control for:

- the effects of expectation;

- the effects of time on confidence, nipple pain and milk transfer;

- as well as the effects of caring attention and breastfeeding support.

Evidence of improvements in comfort and nipple pain following frenotomy is conflicting. At best, there is a maternal subjective sense of improvement over the short term.

Recently, the Human Lactation Research Group at the University of Western Australia (that includes 3 renowned Professors: Hartmann, Geddes, & Douglas) used ultrasound to try to better understand the biomechanics of infant suck during breastfeeding, examining what the tongue is doing. Previously, in 2008, they’d pictured the tongue using a stripping action to extract milk, with a peristaltic wave-like movement drawing the milk out of the breast. If you’ve attended any talks on tongue-tie or read any books or papers, you’ll be sure to have seen this ultrasound examination referred to in support for cutting ties (Geddes, Langton, Gollow, Jacobs, Hartmann, & Simmer, 2008). This time, however, they discovered that the tongue actually has quite a different role to play. What they now say is that peristalsis is a sequential contraction and dilation of tubular muscle, so wasn’t appropriately applied as a concept in the sucking model.

So what is happening during breastfeeding if the previous model was wrong? Douglas and Geddes’ 2018 paper with the new interpretation was published in the journal Midwifery just recently in March and has proved to be quite contentious. Other experts describe what they see differently, so you can take your pick of hypotheses. I may plump for what the 2018 paper says (and author Professor Douglas has confirmed that my understanding in this following simplified summary is correct).

The tip of the tongue rests at the level of the lower gum ridge and does not protrude any further during effective seal and sucking. The tongue does not actively grasp or apply itself to the breast. The tongue is a supple organ that as a moist warm cushion activates the milk ejection reflex. It is not independent movement of the tongue that creates the vacuum in the mouth. As the tongue drops with the lower jaw, more breast tissue is drawn into the mouth. Depression of the lower jaw is what generates the vacuum. The tongue’s capacity to move with the lower jaw is not affected by the frenum. The tongue moves only a matter of millimetres. Consequently, a tethering of the tongue is irrelevant. The tongue does not move laterally during the suck cycle, and effective sucking does not require the tongue to lift independently. The upper lip does not need to flange, it just rests in a neutral position for pain-free milk transfer. White flecks previously seen on ultrasound images are not air bubbles at all, they are fat globules. Others paint a different picture so the disagreement over the tongue’s function illustrates just how little clarity there is.

What is not contentious in their paper is what they say about the power of micro movements or tiny adjustments and the need for mothers to experiment a lot with positioning and attachment. There is no getting round the fact that breastfeeding can be a difficult skill to master, particularly following high intervention births. You may appreciate that a baby’s willingness and ability to breastfeed can be affected by what happens during the birth. Although results suggest that maternal reported nipple pain reduces short term following tongue-tie surgery, milk production and milk intake don’t change significantly, at all.

Cochrane, 2017

A Cochrane review is an independent high quality systematic review that brings together existing primary research to try to establish whether there is conclusive evidence about an intervention. I imagine most people would agree that that is the level of evidence we need when considering surgery on a helpless baby who has no voice in the matter. The 2017 Cochrane review was clear that there is no evidence-based rationale for why surgical intervention might improve breastfeeding outcomes. ‘It is uncertain whether ankyloglossia is a congenital anomaly requiring treatment or a normal variant.’ The small number of trials and their methodological shortcomings limit the certainty of findings in favour of tie surgeries, which have ‘No consistent positive effect on infant breastfeeding.’ ‘Studies to date have not answered the clinically relevant question of whether frenotomy in tongue-tied infants results in longer-term breastfeeding success and resolution of maternal pain.’ ‘Whether frenotomy is a painful procedure that requires analgesia or anaesthesia has yet to be established, as no study to date has quantified infant pain during and after frenotomy’ (O’Shea, Foster, O’Donnell, Breathnach, Jacobs, Todd, & Davis, 2017).

Of course, many health care providers have seen that moment when baby latches on deeply following a tie surgery. And an ultrasound study has shown nipple compression resolve immediately after frenotomy (Geddes, Langton, Gollow, Jacobs, Hartmann, & Simmer, 2008). It is great to empower a mother to go on to be able to breastfeed her baby. Many of us have seen lightbulb moments when mother and baby finally ‘get’ it that have nothing to do with cutting ties, or when babies latch much more deeply following, say, a vaccination or a tumble or other hurt or scare. When a good latch is achieved improvement is immediate. No one has yet established whether untethering the tongue is what fixed breastfeeding rather than the short sharp shock of cutting it.

Moreover, the power of the mind to bend reality as a result of faith, hope and expectation is very strong (have a look at some research on placebos) (Brody & Miller, 2011). When a surgery is being carried out to adapt a baby’s body, isn’t it important to have robust evidence that such a procedure works, especially when such surgery is being done for the potential benefit of someone other than the patient, to relieve the mother’s pain? I think such an operation is actually without precedent. (And, yes of course, I want babies to breastfeed.)

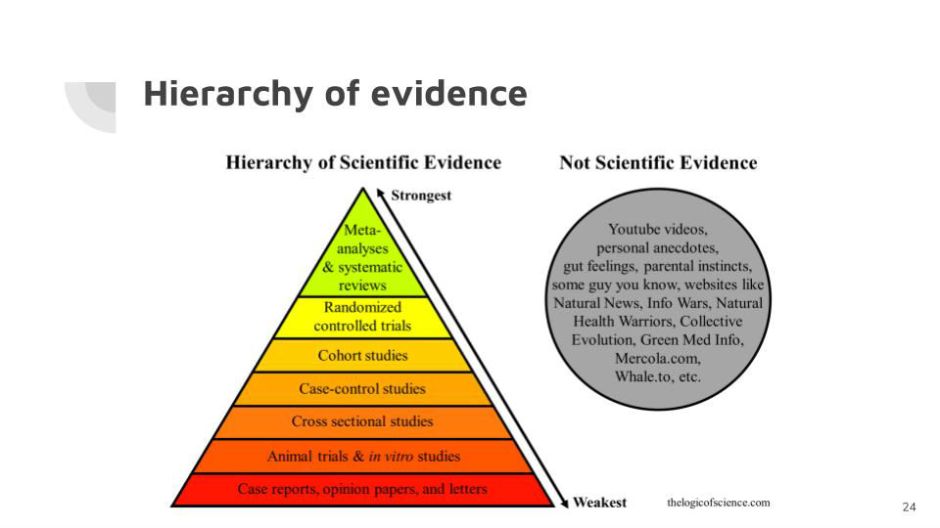

When anyone cites research in support of surgery, see where it comes in the hierarchy of evidence.

This poster was, I believe, designed for use in schools and sums it up well.

About as far as you can stretch the available evidence is to say that in the case of a ‘classic’ anterior tongue-tie tethering the tongue at its tip (that’s a tongue-twister), a small cut to free that tongue may have an immediate effect to allow a baby to achieve a better latch. If it doesn’t, then cutting it was not appropriate.

The burden of proof rests on those recommending surgery to establish its necessity and not on those expressing scepticism about its efficacy.

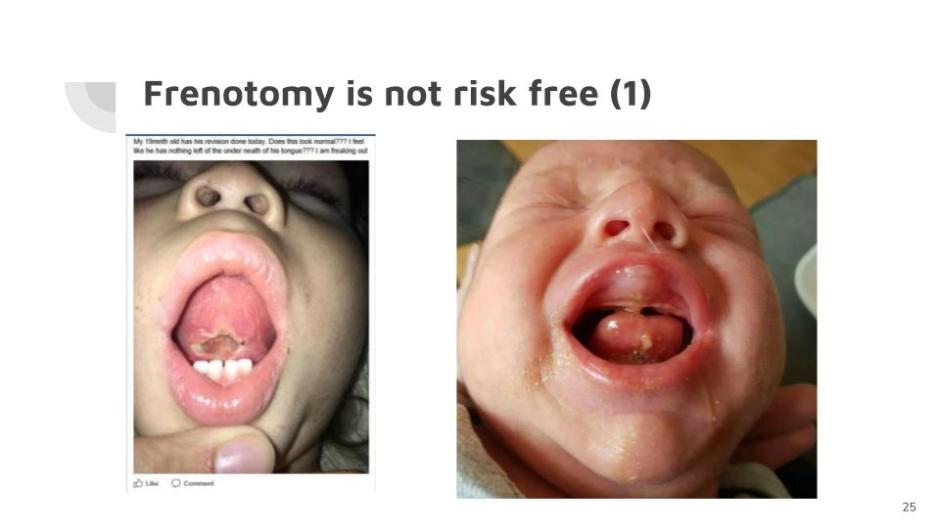

The risks associated with lasering tongue-ties remain unexamined and include

- oral aversion (so not wanting anything in the mouth be it breast or bottle)

- scarring

- thermal burns

- haemorrhage

- wound infection.

—they must be horribly painful.

Is this not mutilation? The following photo was shared by a well known ‘preferred’ provider who was seeking advice on social media.

Disempowering mothers and damaging babies

So, what are mothers saying?

Mothers report improvements in breastfeeding following surgeries on their babies to release ties, believing that this is what saved breastfeeding, and without which breastfeeding would not have been possible. Some mothers report no improvement to breastfeeding following surgeries, and others say that things have become even worse, and that breastfeeding is no longer possible as a result.

I’m horrified by what mothers are sharing on social media about their tie ‘journeys’. If a baby has undergone a frenotomy, then it should have been a quick and painless procedure with minimal down time for recovery. If it wasn’t something is wrong, especially if it was traumatic or when the baby develops an oral aversion and is unable to tolerate having anything in his mouth. On Facebook, there are thousands of mothers posting in specialist tie groups. I’ve documented some of the more common posts and they make for disturbing reading. I’ve lost track of the number of stories I have read along these lines:

His tongue tie was cut and he has been fussy on my boob all day yesterday and only had two small feeds until early this morning. He has been so distressed and is now straight up refusing breast and bottle. I’m so upset cos he looks in agony. I’m scared.

This baby began projectile vomiting and had to be admitted to hospital.

There are also mothers who genuinely believe that without surgery their babies would never have accomplished breastfeeding (or eating solids or speech) and they are at times overly keen to encourage others to follow suit.

There are mothers getting diagnoses from other mothers on the strength of a photo or a list of symptoms; tales of health professionals who accept referrals without taking a full history; mothers for whom the surgery didn’t fix anything and who are feeling guilty, frustrated, overwhelmed. Many are encouraged to seek repeat surgeries in the belief that the cuts didn’t go deep enough or because the ties have reattached. Mothers are encouraged to seek the services of other, often private and pricey, health practitioners for various ‘bodywork’ and other therapies. They are encouraged to persevere with repeated wound stretching exercises to stop the healing and reattachment of the frenum and when a mother voices her reluctance because of her baby’s pain, the group rallies round to urge the mother not to feel guilty: she is not doing it to him, she’s doing it for him, which puts me in mind of the sort of thing that people say in defence of smacking children. Stretching exercises. Why would they help? There is no surgical procedure of any kind after which it is recommended that a wound be actively traumatised in such a way. Often post surgical exercises are scheduled daily for up to 3 weeks. There is no evidence at all to support such harsh aftercare. And to call it ‘gentle massage’ is dishonest.

A story in March this year:

My daughter was 9 weeks old when she got her tie lasered. I’ve never heard her scream like that before, to the point she couldn’t breathe and was drenched in sweat. As soon as they put her in my arms after the procedure, she passed out and slept for hours. It was terrible to witness and I would never do it again.

It’s no surprise that many laser practitioners don’t allow the parents to be present during surgery. The stories of repeat surgeries (some by ‘preferred’ providers), of profuse bleeding and babies ending up being fed by nasogastric tube are chilling. But rather than any realisation that such surgeries were unwarranted, the buzzword now is ‘rehab’ …

One paediatrician said,

If only tongue tie surgeries were benign. Holding children down to perform painful procedures has significant long-term consequences — including central sensitisation to chronic pain, the development of phobias, and aversion that could lead to avoidance of medical and dental healthcare that might actually be necessary in future, thus denying them a real choice about healthcare as they grow up.

Mothers in these ‘support’ groups say that the effects of the surgery may not take effect for some weeks and then, if they still aren’t apparent that surgery was necessary to prevent future issues occurring. Parents are being warned that they run various developmental risks if they don’t proceed with surgery: this idea of long-term dire consequences of the untreated condition frightens many into compliance. Such threats may even increase the chances of reported positive outcomes because of the powerful neurobiological impact of expectation. While laser surgery remains in its infancy, there can be no data to support these notions of preventing long-term consequences.

Instead, we should be asking what the repercussions will be during the next decade or two for these baby guinea pigs. A paediatric dentist, on this subject recently, mentioned how lip-tie surgery can change a baby’s appearance and not in a good way … Will the revised upper lip ride up above the adult teeth in a horse-like fashion? Well intentioned but seriously misguided advice is capable of causing great harm.

Where does the responsibility lie?

In some areas, mothers are being encouraged to see specific lactation consultants for a referral or diagnosis of tongue-tie because others may be less likely to suggest ties are the problem. Some feel pressure to refer to tie practitioners for fear of criticism about ‘missing’ a tie. Have you noticed in breastfeeding groups on social media a tendency by some participants to mention the possibility of tongue-tie before exploring other things that might be causing problems? There are even mothers booking their unborn babies in with dentists for prospective tie surgeries because they ‘know’ that their new baby will have a tie.

An IBCLC may help with breastfeeding problems, but can she address the trauma that results from failed procedures? Perhaps osteopaths or craniosacral therapists, for instance, may be supportive, but do they necessarily have breastfeeding management skills? Some health practitioners from the ever-growing list of disciplines associated with this condition are now adding the IBCLC credential to their professional qualifications.

A mother will stop asking for more breastfeeding advice when there continues to be no improvement. How likely is it she will ever want to see again the practitioner who carried out the surgery? A speech pathologist related how tired she was of repeatedly having to pick up the pieces following failed tongue-tie surgeries. She said:

I saw another baby yesterday who is feeding much worse after a tongue-tie snip. [I’d like to point out that the sort of language we use when talking about surgical procedures can trivialise a baby’s pain. Let’s say “cut” instead of “snip”.] This little baby has lost all suck coordination. Now the mother is having to cup and syringe feed just to get any milk in. I feel it’s my responsibility to fix everything, when I never would have recommended surgery in the first place. I encourage the parents to go back to whoever did the surgery, but often this health professional really has nothing more to offer and the parents feel like it’s a waste of time.

Perhaps the health professional being consulted to pick up the pieces should report back to whoever carried out the frenotomy, so that the practitioner can make a record that this procedure has failed to resolve the problem. But how many have the time to do that? Monitoring of follow-ups is good practice, but there seems little to ensure that it happens.

Effectively the mother disappears.

No surgery is guaranteed and if the wound in the mouth has healed well, you can hardly report the practitioner who performed the surgery for a mother and baby’s failure to succeed at breastfeeding. If the baby is still spitting up or cries a lot, you can’t blame anyone for that either.

One IBCLC said:

It is really hard to suggest to a very distressed mother that she return when the problem has not been resolved.

Sometimes a mother hears that it may take a few months before she will see any improvement following surgery on her baby’s tie and that she still needs to see a whole team of health practitioners from different disciplines. When she starts along this path and her next expensive consultation changes nothing, she may be told that she hasn’t waited long enough to see an improvement. She may hear that she didn’t have the surgery early enough, or that whoever carried out the surgery was not a ‘preferred’ provider. Perhaps, some tell her, she didn’t do the stretches properly, or her baby needs further tie surgeries and/or additional treatments because proponents say this is a multifactorial issue. In other words, no one assumes direct responsibility for the failure of these highly speculative procedures, and such responsibility is easily passed on and often back to the mother herself. It’s not difficult to imagine why she might feel guilty.

For the mother who is psychologically devastated by this whole process, who feels she has lost attachment to her infant, who helps her?

The under-reporting of negative results is a real problem in scientific research.

Negative results are extremely important in science because they indicate what doesn’t work (Kicinski, 2014).

Introducing the idea of tongue-tie worsens parental anxiety and disempowers mothers.

Mothers often are not aware that there are alternative strategies to preserve, facilitate and maintain breastfeeding.

Unrealistic expectations about what is normal young baby behaviour result in pathologising what’s normal. Mothers often don’t know how to follow their babies’ cues (especially when they are made to feel anxious) and are led to believe that fussing necessarily means there is an underlying medical problem, when very often a more responsive approach or repeated minor adjustments to positioning and attachment can fix problems in time, with patience. Breastfeeding is a relationship and, like sex, instructions may be helpful but their application is very individual. It’s not a three-easy-steps how-to type process.

Is it right for anyone to recommend surgery without full, impartial information, for which we need to know that a procedure is safe AND effective in doing what it is supposed to do?

When professionals carrying out surgery are doing procedures with the intention of improving breastfeeding and breastfeeding does not improve, how can a mother fail not to feel undermined and anxious?

It is without precedent to call for surgery on a human being to fix pain in someone other than the patient. Health care providers should respect that vulnerable babies depend on them to keep them safe from harm and they should not carry out surgery if no evidence exists to put babies through it.

To conclude I’d like to quote what the Australian Dental Assoc. President Gary Smith recently said about treating tongue-ties,

If we simply follow dogma, the procedure could be considered on a par with circumcision or the docking of a dog’s tail.

So, please, rock the boat and be brave enough to start a conversation that matters.

My gratitude goes to those health professionals and academics who have corresponded with me on these issues. I thank them for their patience, good humour and integrity.

References (Updated May 2021)

Amir, L. H., James, J. P., & Donath, S. M. (2006). Reliability of the Hazelbaker Assessment Tool for Lingual Frenulum Function. International Breastfeeding Journal, 1(1), 3. doi:10.1186/1746-4358-1-3 (Unreliability of assessment tool.)

Arslan, H., Çandar, T., & Vural, Ö. (2018). Increased anti- EBV VCA IgG antibody levels are associated with need for surgery in patients developing upper respiratory tract complications. International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology, 111, 84–88. doi:10.1016/j.ijporl.2018.05.032 (Viruses cause enlarged adenoids and tonsils. They have nothing to do with mouth breathing or ties.)

Australian Collaboration for Infant Oral Research (ACIOR). (4 October, 2017). Position Statement 1. Upper lip-tie, buccal ties, and the role of frenotomy in infants. (No reason exists to classify diverse variants as ‘upper lip ties’ or buccal ties.)

Australian Dental Association (July 2017). Frenotomy in newborns: Has increased awareness led to unnecessary treatment?

Bambery, D. Dental Council NZ, Practitioners Corner. (July 2017). (Dentists need to be certain that they are clear of the indications for the surgery following adverse outcomes of a serious nature.)

Brody, H., & Miller, F. G. (2011). Lessons from recent research about the placebo effect—from art to science. JAMA, 306(23), 2612. doi:10.1001/jama.2011.1850 (Power of the mind to bend reality as a result of faith, hope and expectation is very strong.)

Braithwaite, J. (2014). The medical miracles delusion. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 107(3), 92–93. doi:10.1177/0141076814523951 (We are more like army ants than we think. ‘Throughout history, mass delusions have been aligned with mass desires for favourable outcomes.’)

Brandão, C. de A., de Marsillac, M. de W. S., Barja-Fidalgo, F., & Oliveira, B. H. (2018). Is the Neonatal Tongue Screening Test a valid and reliable tool for detecting ankyloglossia in newborns? International Journal of Paediatric Dentistry, 28(4), 380–389. doi:10.1111/ipd.12369 (Neonatal Tongue Screening Test is neither reliable nor valid for detecting ankyloglossia that may interfere with breastfeeding in newborns.)

Brooks, E. (2013). Legal and ethical issues for the IBCLC. Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett. (Who is responsible?)

Brownlee, S., Chalkidou, K., Doust, J., Elshaug, A. G., Glasziou, P., Heath, I., … Korenstein, D. (2017). Evidence for overuse of medical services around the world. The Lancet, 390(10090), 156–168. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(16)32585-5

Buryk, M., Bloom, D., & Shope, T. (2011). Efficacy of neonatal release of ankyloglossia: A randomized trial. PEDIATRICS, 128(2), 280–288. doi:10.1542/peds.2011-0077 (Effect of frenotomy is immediate.)

Caloway, C., Hersh, C.J., Baars, R., Sally, S., Diercks, G., Hartnick, C.J. (2019). Association of feeding evaluation with frenotomy rates in infants with breastfeeding difficulties. JAMA Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2019 Sep 1;145(9):817-822. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2019.1696. PMID: 31294774; PMCID: PMC6624821. (There remains insufficient evidence that frenotomy for ankyloglossia is associated with improvements in breastfeeding. Clear indications for surgical release remain murky. A majority of patients referred for tongue-tie may benefit from alternative intervention strategies following comprehensive feeding evaluation.)

Coryllos E, Watson Genna C, Salloum A. (2004, Summer). Congenital tongue-tie and its impact on breastfeeding. Breastfeeding: Best for mother and baby, American Academy of Pediatrics Newsletter, 1–6. (Idea of posterior ties introduced.)

Douglas, P. (2013). Diagnosing gastro-oesophageal reflux disease or lactose intolerance in babies who cry a lot in the first few months overlooks feeding problems. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health, 49(4), E252–E256. doi:10.1111/jpc.12153 (The idea of medicalising fussing.)

Douglas, P. (2017). Making sense of studies that claim benefits of frenotomy in the absence of classic tongue-tie. Journal of Human Lactation, 33(3), 519–523. doi:10.1177/0890334417706694 (Studies confuse association with causation.)

Douglas, P., & Geddes, D. (2018). The latest practice-based interpretation of ultrasound studies leads the way to more effective clinical support and less pharmaceutical and surgical intervention for breastfeeding infants. Midwifery, 58,145–155. doi:10.1016/j.midw.2017.12.007 (Abandons previous sucking model and adopts one that illustrates tied babies can breastfeed with better positioning and attachment.)

Fraga, M.D.R.B.A., Barreto, K.A., Lira, T.C.B., Menezes, V.A. (2021). Diagnosis of ankyloglossia in newborns: is there any difference related to the screening method? Codas. 2021 May 3;33(1):e20190209. Portuguese, English. doi: 10.1590/2317-1782/20202019209. PMID: 33950147. (The ankyloglossia diagnosis in newborns varied depending on the assessment instrument used.)

Geddes, D. T., & Sakalidis, V. S. (2016). Ultrasound imaging of breastfeeding—A window to the inside. Journal of Human Lactation, 32(2), 340–349. doi:10.1177/0890334415626152 (Description of the tongue movements during sucking as seen in new ultrasound images.)

Geddes, D. T., Langton, D. B., Gollow, I., Jacobs, L. A., Hartmann, P. E., & Simmer, K. (2008). Frenulotomy for breastfeeding infants with ankyloglossia: Effect on milk removal and sucking mechanism as imaged by ultrasound. PEDIATRICS, 122(1), e188–e194. doi:10.1542/peds.2007-2553 (nipple compression resolving immediately after frenotomy).

Grond, S.E., Kallies, G., McCormick, M.E. (2021). Parental and provider perspectives on social media about ankyloglossia. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. Apr 28;146:110741. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijporl.2021.110741 (Demonstrates the spectrum of opinions that exist among both parents and providers about ankyloglossia. A large amount of non-scientific information and opinions is disseminated that may be shaping decisions.

Haham, A., Marom, R., Mangel, L., Botzer, E., & Dollberg, S. (2014). Prevalence of breastfeeding difficulties in newborns with a lingual frenulum: A prospective cohort series. Breastfeeding Medicine, 9(9), 438–441. doi:10.1089/bfm.2014.0040 (A lingual frenulum is a normal anatomical finding whose insertion point and Coryllos classification are not correlated with breastfeeding difficulties.)

Hale, M., Mills, N., Edmonds, L., Dawes, P., Dickson, N., Barker, D., Wheeler, B.J. (2020). Complications following frenotomy for ankyloglossia: A 24-month prospective New Zealand Paediatric Surveillance Unit study. J. Paediatr. Child Health. 2020 Apr;56(4):557-562. doi: 10.1111/jpc.14682. (Frenotomy rates in New Zealand are unknown. Poor feeding, pain, bleeding, weight loss and delayed diagnosis of an alternative underlying medical condition are important complications that require hospital assessment and admission. Practitioners and parents/families need to be aware of these possibilities. Centralised guidelines with access to specialist second opinions should be developed.)

Hatfield, L. (2014). Neonatal pain: What′s age got to do with it?

Surgical Neurology International, 5(14), 479. doi:10.4103/2152-7806.144630 (The neurobiology of neonatal pain processing.)

Hazelbaker, A. K. (1993). The assessment tool for lingual frenulum function: use in a lactation consultant private practice (Master’s thesis). Pacific Oaks College, Pasadena, CA.

Hoffmann, T. C., & Del Mar, C. (2017). Clinicians’ expectations of the benefits and harms of treatments, screening, and tests. JAMA Internal Medicine, 177(3), 407. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.8254 (We can’t trust clinicians’ perceptions about the benefits and harms of surgical interventions. Unjustified enthusiasm for treatment.)

Hoffmann, T. C., & Del Mar, C. (2015). Patients’ expectations of the benefits and harms of treatments, screening, and tests. JAMA Internal Medicine, 175(2), 274. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.6016 (Patients have inaccurate expectations, and most think that interventions will help more and harm less than they actually do.)

Hong, P., Lago, D., Seargeant, J., Pellman, L., Magit, A. E., & Pransky, S. M. (2010). Defining ankyloglossia: A case series of anterior and posterior tongue ties. International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology, 74(9), 1003–1006. doi:10.1016/j.ijporl.2010.05.025 (Retrospective case series mentioning posterior ties.)

Ingram, J., Johnson, D., Copeland, M., Churchill, C., Taylor, H., & Emond, A. (2015). The development of a tongue assessment tool to assist with tongue-tie identification. Archives of Disease in Childhood – Fetal and Neonatal Edition, 100(4), F344–F349. doi:10.1136/archdischild-2014-307503

Isaacs, D. Tongue-tie and frenotomy. (2015). Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health, 51(2), 227–228. doi:10.1111/jpc.12846_3 (If frenotomy is being performed despite evidence that it is ineffective, this raises ethical concerns. Report of neonatal Staphylococcus aureus septicaemia as a major complication suggests frenotomy may not be as safe as some claim.)

Joseph, K. S., Kinniburgh, B., Metcalfe, A., Razaz, N., Sabr, Y., & Lisonkova, S. (2016). Temporal trends in ankyloglossia and frenotomy in British Columbia, Canada, 2004–2013: A population-based study. CMAJ Open, 4(1), E33–E40. doi:10.9778/cmajo.20150063 (Diagnostic suspicion bias and increasing use of potentially unnecessary surgical procedures.)

Kapoor, V., Douglas, P. S., Hill, P. S., Walsh, L. J., & Tennant, M. (2018). Frenotomy for tongue-tie in Australian children, 2006-2016: an increasing problem. The Medical Journal of Australia, 208(2), 88–89. doi:10.5694/mja17.00438 (An epidemic.)

Kaptchuk, T. J. (2003). Effect of interpretive bias on research evidence. BMJ, 326(7404), 1453–1455. doi:10.1136/bmj.326.7404.1453 (E.g. the failure to control for multiple potential confounders and the effects of expectation; the effects of time on confidence, nipple pain and milk transfer; and the effects of caring attention and breastfeeding support.)

Kicinski, M. (2014). How does under-reporting of negative and inconclusive results affect the false-positive rate in meta-analysis? A simulation study. BMJ Open, 4(8), e004831–e004831. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2014-004831 (Negative results are extremely important in science because they indicate what doesn’t work.)

Kotlow, L. (2011). Diagnosis and treatment of ankyloglossia and tied maxillary fraenum in infants using Er:YaG and 1064 diode lasers. European Archives of Paediatric Dentistry, 12(2), 106–112. doi:10.1007/bf03262789 (Kotlow was an early user of lasers to treat posterior ties.)

Kotlow, L. (2011). Infant reflux and aerophagia associated with the maxillary lip-tie and ankyloglossia (Tongue-tie). Clinical Lactation, 2(4), 25–29. doi:10.1891/215805311807011467 (He thinks babies with ties swallow air.)

Martinelli, R. L. de C., Marchesan, I. Q., Lauris, J. R., Honório, H. M., … Gusmão, R. J. (2016). Validade e confiabilidade da triagem: “teste da linguinha.” Revista CEFAC, 18(6), 1323–1331. doi:10.1590/1982-021620161868716

Matosin, N., Frank, E., Engel, M., Lum, J. S., & Newell, K. A. (2014). Negativity towards negative results: a discussion of the disconnect between scientific worth and scientific culture. Disease Models & Mechanisms, 7(2), 171–173. doi:10.1242/dmm.015123 (Too many failed frenotomies go unreported.)

Mills, N., Pransky, S.M., Geddes, D.T., Mirjalili, S.A. (2019). What is a tongue tie? Defining the anatomy of the in-situ lingual frenulum. Clin Anat. 2019 Sep;32(6):749-761. doi: 10.1002/ca.23343. (This new understanding of frenulum anatomy highlights the potential risks or complications involved in surgical intervention.)

Morgan, D. J., Brownlee, S., Leppin, A. L., Kressin, N., Dhruva, S. S., Levin, L., … Elshaug, A. G. (2015). Setting a research agenda for medical overuse. BMJ, h4534. doi:10.1136/bmj.h4534

Naimer, S.A., Israel, A., Gabbay, A. (2021). Significance of the tethered maxillary frenulum: a questionnaire-based observational cohort study. Clin. Exp. Pediatr. Mar;64(3):130-135. doi: 10.3345/cep.2020.00486. (A tethered labial frenulum is not associated with an increase in breastfeeding disturbances or oral disorders. These data encourage clinicians to question the need to intervene in cases of tethered maxillary frenula.)

Nakhash, R., Wasserteil, N., Mimouni, F.B.,Kasirer, Y.M., Hammerman, C., Bin-Nun, A. (2019). Upper lip tie and breastfeeding: A systematic review. Breastfeeding Medicine, https://doi.org/10.1089/bfm.2018.0174 (Routine upper lip tie release cannot be recommended. The classification system proposed by Kotlow is unreliable both in terms of inter and intraobserver agreement and in terms of predicting the severity of the breastfeeding difficulties.)

NZ Dental Association. (April, 2018) Position statement. Ankyloglossia and frenal attachments. (Substantial and unjustified increase in surgical management. Condition resolves with growth in most cases. Data suggest the majority do not exhibit breastfeeding problems.)

O’Shea, J. E., Foster, J. P., O’Donnell, C. P., Breathnach, D., Jacobs, S. E., Todd, D. A., & Davis, P. G. (2017). Frenotomy for tongue-tie in newborn infants. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd011065 (‘No consistent positive effect on infant breastfeeding’.)

Palmer, G. The politics of breastfeeding: When breasts are bad for business. ISBN: 9781905177165 and Why the politics of breastfeeding matter ISBN: 9781780665252 (I see parallels between what Palmer writes on the promotion of artificial formula and ties surgery.)

Power, R. F., & Murphy, J. F. (2014). Tongue-tie and frenotomy in infants with breastfeeding difficulties: achieving a balance: Table 1. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 100(5), 489–494. doi:10.1136/archdischild-2014-306211 (50% of babies with ties encounter no problems breastfeeding.)

Reid N, & Rajput N. (2014). Acute feed refusal followed by Staphylococcus aureus wound infection after tongue‐tie release. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health, 50(12) 1030–1031. doi.org/10.1111/jpc.12773 (Case report highlights that ‘simple’ scissors frenotomy is not always effective and can result in significant adverse effects. The presence of mastitis or nipple infection in the mother may increase risk of wound infection.)

Santa Maria, C., Aby, J., Truong, M. T., Thakur, Y., Rea, S., & Messner, A. (2017). The superior labial frenulum in newborns: What is normal? Global Pediatric Health, 4, 2333794X1771889. doi:10.1177/2333794×17718896 (Given the lack of knowledge surrounding the function of the upper frenulum, the ubiquity of its presence, and level of attachment in most infants, the release of the superior labial frenulum based on appearance alone cannot be endorsed at this time.)

Shah, S., Allen, P., Walker, R., Rosen-Carole, C., McKenna Benoit, M.K. (2021). Upper lip tie: Anatomy, effect on breastfeeding, and correlation with ankyloglossia. 2 Laryngoscope. May;131(5):E1701-E1706. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.29140 (No correlation between maxillary frenulum grade and comfort with breastfeeding, pain scores, or latch. No relationship between tip to frenulum length (tongue tie) and visualized lip anatomy, suggesting that tongue-tie and lip tie may not cluster together in infants.)

Smith, G., Australian Dental Association Queensland President (September 2017) ADA News Bulletin. (Raises concerns about the procedures on infants.)

Smith, G., Australian Dental Association Queensland President (December 2017) ADA News Bulletin, 643, 5–6. (‘Not surprisingly, there are many half-truths and fallacies pushed by those who promote tongue tie surgery for financial gain.’)

Teixeira da Silva, J. A. (2015). Negative results: negative perceptions limit their potential for increasing reproducibility. Journal of Negative Results in Biomedicine, 14, 12. doi:10.1186/s12952-015-0033-9

Tracy, L. F., Gomez, G., Overton, L. J., & McClain, W. G. (2017). Hypovolemic shock after labial and lingual frenulectomy: A report of two cases. International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology, 100, 223–224. doi:10.1016/j.ijporl.2017.07.013 (The dreadful damage that does happen.)

USLCA, The tongue-tie controversy. (2017) Clinical Lactation 8(3), 87–143. (Round-table discussion amongst tie experts. I refer to the question about prevalence and incidence of the condition and the assessment tool references are here.)

Walsh, J., Links, A., Boss, E., & Tunkel, D. (2017). Ankyloglossia and lingual frenotomy: National trends in inpatient diagnosis and management in the United States, 1997–2012. Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, 156(4), 735–740. doi:10.1177/0194599817690135 (Epidemic.)

Wang, J., Yang, X., Hao, S., Wang, Y. (2021). The effect of ankyloglossia and tongue-tie division on speech articulation: A systematic review. Int. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2021 May 8. doi: 10.1111/ipd.12802. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 33964037. (There is no clear connection between ankyloglossia and speech disorders.)

A list of my blog posts

Always Ask Questions: Don’t Let Your Tongue Be Tied

Did Tongue-Tie Release Fail to Improve Problems?

Does Tongue-Tie Disempower Mothers and Damage Babies?

How Credible Is The Current Oral Tie Trend?

Is The Current Breastfeeding Problem a Fault in Babies’ Mouths?

Is The Treatment of Tongue-Tie an ‘Unjustified Enthusiasm’?

Reading Between the Lines Post-Tie Surgery

Snipping Tongue-Ties. Whose Business?

Spinning a Web: Spiders and Tongue-Ties

Surgery on Babies: Does it Hurt?

The New Sucking Model and Tongue-Tie

Tongue-Tie Epidemic Poses Risk to Community

Tongue-Tie Politics of Breastfeeding

When Releasing Tongue-Ties Does Not Fix Breastfeeding

Who Diagnoses Tongue-Ties that Interfere With Breastfeeding?